While cloudy skies aid in controlling Earth’s climate, researchers have yet to fully understand the principles behind cloud formation. However, the scientific community has now moved one step closer to correcting this.

Researchers from the University of Washington and the Pacific Northwest National Laboratory have discovered that tiny organisms inhabiting large stretches of the ocean’s water column, called plankton, play a crucial role in illuminating clouds and shielding the planet from radiation.

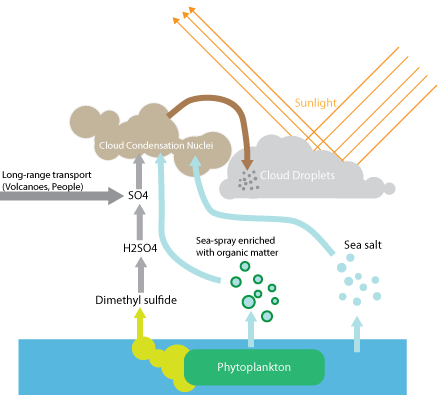

The team found that plankton produces organic matter and airborne gases that “seed cloud droplets.” In turn, this leads to much brighter clouds that more readily reflect the sun’s rays.

The researchers explained the phenomenon in their latest paper: “Atmospheric aerosols, suspended solid and liquid particles, act as nucleation sites for cloud drop formation, affecting clouds and cloud properties—ultimately influencing the cloud dynamics, lifetime, water path, and areal extent that determine the reflectivity (albedo) of clouds.”

According to Daniel McCoy, a University of Washington student of atmospheric sciences, during the summer months, the cloud formations over the Southern Ocean help to reflect more sunlight. McCoy and colleagues claim there would be halve the concentration of cloud droplets, in the event we had a “biologically dead ocean.”

In collaboration with study co-author Daniel Grosvenor, McCoy first embarked upon his research in 2014. The pair investigated the cloud formation over ice-free stretches of the Southern Ocean, using round-the-clock information from NASA satellites.

Using said data, the researchers were surprised to find that the clouds in these regions of water were primarily composed of tiny droplets in the summertime. According to existing theories, the droplets should be relatively large in the summer, because the calmer seas should cast off less salt from sea spray.

This is where co-lead author Susannah Burrows, of the Pacific Northwest National Lab, came into the picture. Burrows used a new ocean model to determine the role of biological matter in cloud formation.

She found that Sulfitobacter and phytoplankton emit sulfide gases that seed cloud droplets, while organic matter on the water’s surface forms a scummy layer that gets blasted into the atmosphere by the choppy oceans. Representing tiny pieces of dead plants and animals, these droplets are wafted into the air.

Burrows took the opportunity to explain the ensuing chemical processes that take place in the Earth’s atmosphere:

“The dimethyl sulfide produced by the phytoplankton gets transported up into higher levels of the atmosphere and then gets chemically transformed and produces aerosols further downwind, and that tends to happen more in the northern part of the domain we studied. In the southern part of the domain there is more effect from the organics, because that’s where the big phytoplankton blooms happen.”

The study, entitled Natural aerosols explain seasonal and spatial patterns of Southern Ocean cloud albedo, was published in the July 17 issue of the journal Science Advances.

Top image credit: Stewart Baird / Flickr